Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

How Minnesota cops are making Mogadishu safer and why it matters for Minnesota

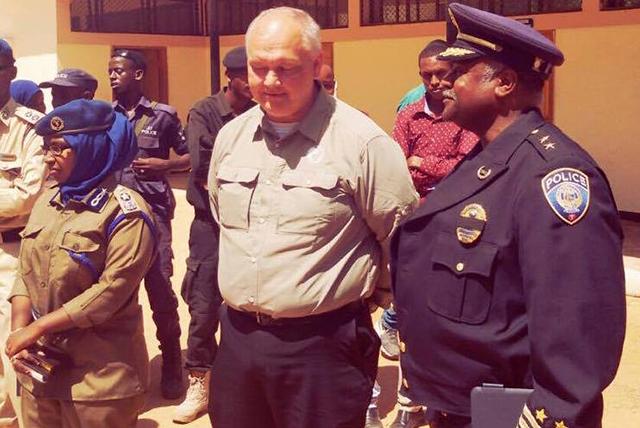

Metro Transit Police Chief John Harrington, right, and Three Rivers Park District Police Chief Hugo McPhee visited Mogadishu in July to distribute donated police equipment.

Metro Transit Police Chief John Harrington, right, and Three Rivers Park District Police Chief Hugo McPhee visited Mogadishu in July to distribute donated police equipment.

The first time Metro Transit Police Chief John Harrington visited Mogadishu, he was startled when he saw Somali criminal investigators and police forces respond to terrorist attacks — they had no bulletproof vests or other safety equipment.

Later, Harrington learned that the Somali government — which depends on foreign aid to maintain its personnel — is unable to provide protective gear for law enforcement. “Vests for the officers were the exception, not the rule,” he said in a recent interview in his Minneapolis office. “The government has been working through the international community just to get uniforms for everybody.”

That was a year ago. After Harrington returned to Minnesota from the weeklong visit to Somalia, he spent months connecting with police agencies throughout the state, asking them if they had surplus equipment they would be willing to donate to the East African nation.

The response was overwhelming: In six months, Harrington collected 1,700 pounds of equipment from various Minnesota police departments, including Moorhead, Savage and the Three Rivers Park District.

“I’m not surprised that they would donate materials,” Harrington said earlier this month of the police agencies. “But I had no idea that it was going to be 11 pallets and almost one ton of materials.”

The support isn’t just a feel-good effort, though. Nine years ago, al Shabab, an al Qaeda linked group, recruited more than 20 Somali-American college and high school students from Minnesota, sparking alarm in the Somali community and among U.S. intelligence agencies. Since then, and amid intensifying terror recruitment concerns in the Twin Cities, U.S. law enforcement has increased its collaboration with the East African country, which has seen decades of violence that’s uprooted hundreds of thousands of people to Minnesota, Canada, Europe and other parts of the world.

“I really believe that if Mogadishu is safer, the Twin Cities is safer,” said Harrington, who also served as a former St. Paul police chief and a state senator. “The two cities are not disconnected. They’re directly connected.”

Visit sparks idea

In 2015, Metro Transit Police Sgt. Waheid Siraach took a yearlong leave of absence from the department to go to Somalia to train 100 police officers on crime investigation through a State Department-funded program.

Midway into the training, Siraach facilitated a trip that brought his chief from Minnesota, Harrington, to Mogadishu in order to show his boss the work he’d been doing in his native Somalia.

Harrington became the first police chief from Minnesota to visit Somalia. “The work he was doing to create this criminal investigation division was already showing great benefit,” Harrington said. “Before, the training, you’d have an explosion from al-Shabab attackers, for example, and only the military would come in. There was no civil policing response.”

Waheid Siraach took a yearlong leave of absence from his job in 2015 to train police officers in Somalia.

In part, that’s because the current U.S.-backed Somali government still struggles to shake off the decades-long political confusion and social turmoil the country has suffered since clan-based militia groups overthrew President Mohamed Siad Barre’s regime in 1991.

By the time Harrington got to Mogadishu, however, he said he noticed Siraach’s training bearing fruit: The Somalia government wasn’t just relying on its military after an attack in the city; it finally had newly trained criminal detectives who were responding to hot zones and conducting investigations.

In that first visit, Harrington also met with Somalia’s top law enforcement officials to talk about ways Minnesota and Mogadishu police agencies could collaborate and further improve their relationships. And when Siraach’s training completed in December, he led a delegation of senior Somali police officers to Minnesota, where they met city and county law enforcement officials. “We took them to the airport and talked about what would airport security look like from a civil policing perspective,” Harrington said. “They really didn’t have a very robust airport police at that time.”

A transformed city

In addition to training and exchange assistance, the Somali police force officers requested protective equipment for officers who work in dangerous areas.

That’s what sparked Harrington’s idea to reach out to various police departments in Minnesota to see if they had gently used police equipment they could donate.

The state government funds police safety equipment such as bulletproof vests, which are replaced after five years. “They’re still good vests, they have never been shot, they have never been dunked in water,” Harrington said. “But the company that manufactures them provides new vests after five years.”

The police departments had enough in their storage to donate: In six months, Harrington had $125,000-worth of equipment: vests, uniforms, helmets and light bars. And this past July, Harrington took a personal vacation from his job again to travel to Mogadishu in order to deliver the donated equipment to Somali police forces and to see the progress the city has made. “I was amazed to see how the city has improved,” he said. “There were things I got glimpses of during my first trip that have now become full-blown operational entities that are really functioning at an incredibly high level.”

What’s in it for Minnesota?

When Harrington was Chief of the St. Paul Police Department between 2004 and 2010, he saw several criminal cases involving Somali-Americans that ended in mystery. “We had young people that were involved in homicides in the Twin Cities,” he said. “When we turned up the heat on them, they went back home. At that time, there was no civil government [in Mogadishu] to contact and say, ‘If you find him, send him back.’”

Today, he said, Minnesota law enforcement agencies have a much better relationship with their counterparts in the East African nation. They have connections with senior government officials and law enforcement agencies — and thus are better equipped to bring back those who escape after committing a crime in Minnesota.

Several Minnesota police agencies donated $125,000 worth of equipment to the Somali police force in Mogadishu this summer.

“The more relationships there, the better are the chances we will be able to bring [criminals] to justice,” Harrington said. “I see this as having benefits both in terms of the terrorist issue, but also just in terms of policing and crime deduction.”

Siraach, who in 2013 became the first Somali-American sergeant anywhere in the United States, added that Somalia and the U.S. have a common enemy: ISIS and al-Shabab. “We know those groups have recruited young Somalis from Minnesota and other states,” he said. “We also know that they thrive in countries where there are conflicts. We understand that a stable and peaceful Somalia is good for the security of Minnesota and that of the United States — and perhaps the entire world. Insecurity in Somalia is insecurity everywhere.”

What’s next?

Harrington returned to Minnesota earlier this month after delivering the donation to Mogadishu police agencies — but he says that he’s not done yet. He’s currently working with the Minneapolis Police Department to host Somali detectives who will be trained in American police procedures. “We have a half dozen police departments who have said they would be interested and willing to be the host agency when the Somali police officers make their trip over.”

Harrington said he’s working to find ways to donate aging ambulances and police squad cars that Minnesota police departments and the Hennepin County Medical Center would deem too old for continued services.

Harrington, who began his law enforcement career with the St. Paul Police Department in 1977 and was sworn in as chief with the Metro Transit Police in 2012, is also looking into the old video surveillance equipment of the Twin Cities police departments.

“The Twin Cities have been using closed-circuit television in their downtown areas for — in the case of Minneapolis — well over 15 years,” he said. “You know that equipment has gone from analogue equipment to digital equipment to high definition equipment. My question is, what happens to the old equipment?”

He’s in the process of reaching out to police departments to see if they’re willing to donate used video surveillance equipment to their Somali counterparts in Mogadishu, a move that continues a history of Minnesota city governments donating used equipment to other parts of the word. Earlier this year, for example, Minneapolis donated two used firetrucks and a crime-lab van to its sister city of Bosaso, Somalia — after members of the City Council’s Intergovernmental Relations Committee voted to approve the donation.

Source: www.minnpost.com

Figradihiina